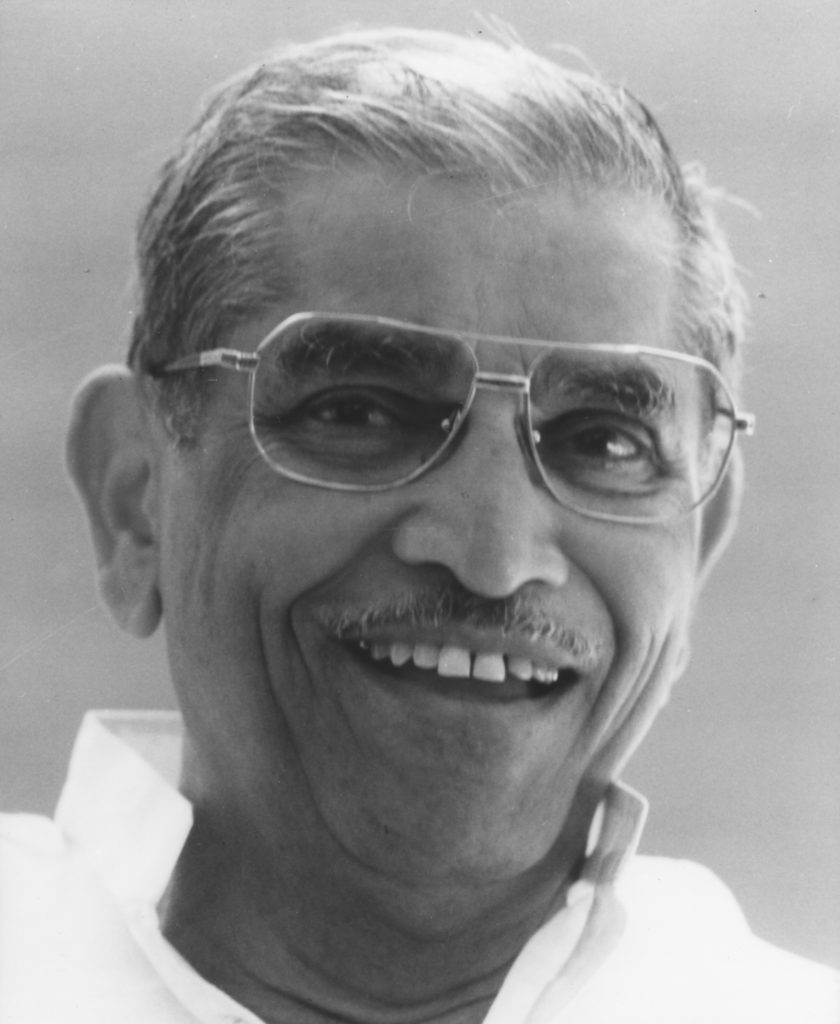

NEW YORK, March 5, 1997 — Pandurang Shastri Athavale, founder and leader of a spiritual self-knowledge movement in India that has liberated millions from the shackles of poverty and moral dissipation, has won the 1997 Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion. The announcement of the award was made at a news conference today at the Church Center for the United Nations.

In honor of the 25th anniversary of the prize, H.R.H. Prince Philip will present the award to Pandurang Shastri Athavale at a public ceremony, scheduled to be held in Westminster Abbey on May 6th. Begun in 1972 by renowned global investor Sir John Templeton, the prize is given each year to a living person who has shown extraordinary originality in advancing humankind’s understanding of God and/or spirituality. The Templeton Prize — valued at 750,000 pounds sterling, about $1.21 million — is the world’s largest annual monetary award.

With less than 20 co-workers in 1954, Athavale (pronounced Ah-TAH-vah-lee), 76, began bhaktiferi (devotional visits) to the villages around Bombay to spread a message of love for God and love for all people, considered by the workers to be God’s children. Believing in self-knowledge as the preliminary condition for an inner growth that leads to a loving, enlightened, social concern and outreach, Athavale initiated the practice of swadhyaya — a Sanskrit word that roughly translates to self-study.

Swadhyaya (pronounced swah-DEE-ah) has spread to nearly 100,000 villages across India and is estimated to have directly improved the lives of 20 million people. Based on the Bhagavad Gita (Song of God), the holiest text in the Hindu religion, Athavale’s philosophy asks people to recognize the inner presence of God which, he says, leads to a sense of self-esteem as well as an awareness of the divine presence within all persons. Again and again throughout India and other parts of the world, this belief that all persons are divine brothers and sisters in the family of God has led to the betterment of individuals and communities.

So vast is the sweep of Athavale’s efforts that it has been compared to the social revolution of Mahatma Gandhi. But, while Gandhi advocated equal rights for India’s so-called “untouchables,” Athavale’s Brahman swadhyayees (pronounced swah-dee-AAYS) openly mix with all other classes, an act unheard of during the strict caste system of Gandhi’s time. And when class and religious riots swept India in recent years, Athavale’s swadhyaya villages were free of strife.

Pandurang Shastri Athavale — referred to as “Dada” by his co-workers, an affectionate term that means “elder brother” — has specifically sought to bring into the mainstream of society communities long treated as outsiders by caste Hindus. Among those who have benefitted most are the fishing villages of India, where gambling, drinking, and wife and child abuse have been replaced with cooperative efforts that have spiritually elevated the downtrodden, vastly reduced crime, and fed the poor. It has also dramatically improved the economic outlook for the communities. Increased attention to personal and community hygiene have resulted in a marked decline in health problems.

Since its founding, swadhyaya — which teaches equal respect for all religions, races, and creeds — has spread across the subcontinent and is now active in nations around the world, including the United States, Canada, Germany, Sweden, Portugal, Kenya, South Africa, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Fiji, the West Indies, and Surinam.

The ‘Silent’ Revolution

Athavale’s work is often described as a “silent” revolution in that it has starkly changed the lives of so many people, yet has succeeded with a minimum of fanfare. Most notably, it has been conducted with virtually none of the negative attributes often associated with the spread of a spiritual movement. It has no formal hierarchy and not a single paid worker. Proselytizing is discouraged. According to Athavale, a person must first be a good Christian, Jew, Muslim or other devotee in order to be a swadhyayee. Swadhyaya, he says, is best shared by example and heart to heart and mind to mind discussion.

Swadhyayees seek no private or public funding. Even unsolicited donations are declined. When Athavale received the prestigious Mahatma Gandhi Prize in 1988, he doubled the amount of the prize and returned it to its donors to be used as they saw fit.

Swadhyaya is also bringing positive changes to the environment. Swadhyayees have joined together to lease plots of land in Maharashtra and Gujarat which have resulted in new orchards and forests in places once barren. They tend the trees on a rotational basis as devotion to God. The survival rate for these groves, known as vrikshmandir (orchards for God), is nearly 100 percent. They have followed similar practices in establishing yogeshwar krushis (farms for God) where each swadhyayee within the villages has an opportunity to work on the farms several days a year as a form of loving devotion.

In nominating Athavale, Texas A&M University professor Betty M. Unterberger wrote:

“A spiritual revolution has created an increased awareness of God within and a spirit of self-esteem, self-confidence and self-reliance…. Motivated by a deep commitment to the service of God’s work, Athavale has sought nothing less than the creation of a divine world undergirded by a divine current of thought.”

In a statement prepared for the press conference today, Athavale said:

“This Award is to advance human spirit’s quest for love and understanding of God and expansion of spiritual resources. I see it as a tribute to the conviction that existence of God is central to life and true religion is the guiding principle of life.

“Through Swadhyaya way of thinking and life, I have tried to activate a sense of Divine by raising the consciousness of being the children of the same God through thoughts and purposive collective action for common good. It is my experience that awareness of nearness of God and reverence for that power creates reverence for self, reverence for the other and reverence for the entire creation. And devotion as an expression of gratitude to God can turn into a social force to bring about transformative changes in all aspects of life and at all levels in the society.”

Athavale’s receipt of the award follows something of a pattern in the Templeton Prize. While many Templeton Prize winners are well-known personalities — such as Mother Teresa, who won in 1973, 1982’s winner Rev. Dr. Billy Graham, and 1983 recipient Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — most have earned the prize through pursuits often removed from the public eye. In 1995, for example, mathematical physicist Paul Davies won the Templeton Prize for his wide-ranging inquiries into the workings of the universe that breach the barrier between science and religion. Last year’s recipient was Bill Bright, president and founder of Campus Crusade for Christ International.

Pandurang Shastri Athavale: Background

Athavale was born to Brahman parents in 1920 in the village of Roha near Bombay. His father, Shri Vaijnath Laxman Athavale Shastri, founded the Shrimad Bhagavad Gita Pathshala, a seat of Vedic learning in Bombay. His grandfather, a headmaster and Vedic scholar, started a private school to teach the young Athavale classic literature, comparative religions, Eastern and Western philosophy, logic, history, several languages, including English, Sanskrit and Hindi, Vedic scriptures, grammar, physics and various social sciences. His education also included intensive reading at Bombay’s Royal Asiatic Society Library.

By his early twenties, Athavale started gaining popularity from his teaching and preaching of the Bhagavad Gita, winning the respect of people around him with the integrity of his character and the power of his message. Among his most significant messages is that of devotion to God through an awareness that God dwells within each person. Work is worship, according to Athavale, when it is done in devotion to God.

In 1954, Athavale was invited to present a series of lectures at the Second World Religious conference in Tokyo. There, his interpretation of the Bhagavad Gita received an enthusiastic reception from fellow delegates who offered him various positions in philosophy and religion in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Athavale refused, choosing instead to return to India with the aim of establishing a community living by the ideals of the Bhagavad Gita. Now, more than four decades later, that singular goal has made a positive difference for millions of people, breaking barriers of caste, reforming lives of crime and abuse, bringing care for the needy, and fostering a political revolution of cooperation, creative decision making and equality for all without regard for race, class, or religion. In recognition of those incredible strides, Athavale has been awarded the 1997 Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion.